أدناه يمكنك قراءة الترجمة الإنجليزية لهذا المحتوى المترجم بواسطة مترجم بشري. يمكنك أيضًا عرض الأصل باللغة الإسبانية من خلال النقر على العلم المقابل في الزاوية اليمنى العليا. يتيح لك هذا الرابط الوصول إلى نسخة من الترجمة الآلية من Google للعربية: https://bit.ly/3e1Figx

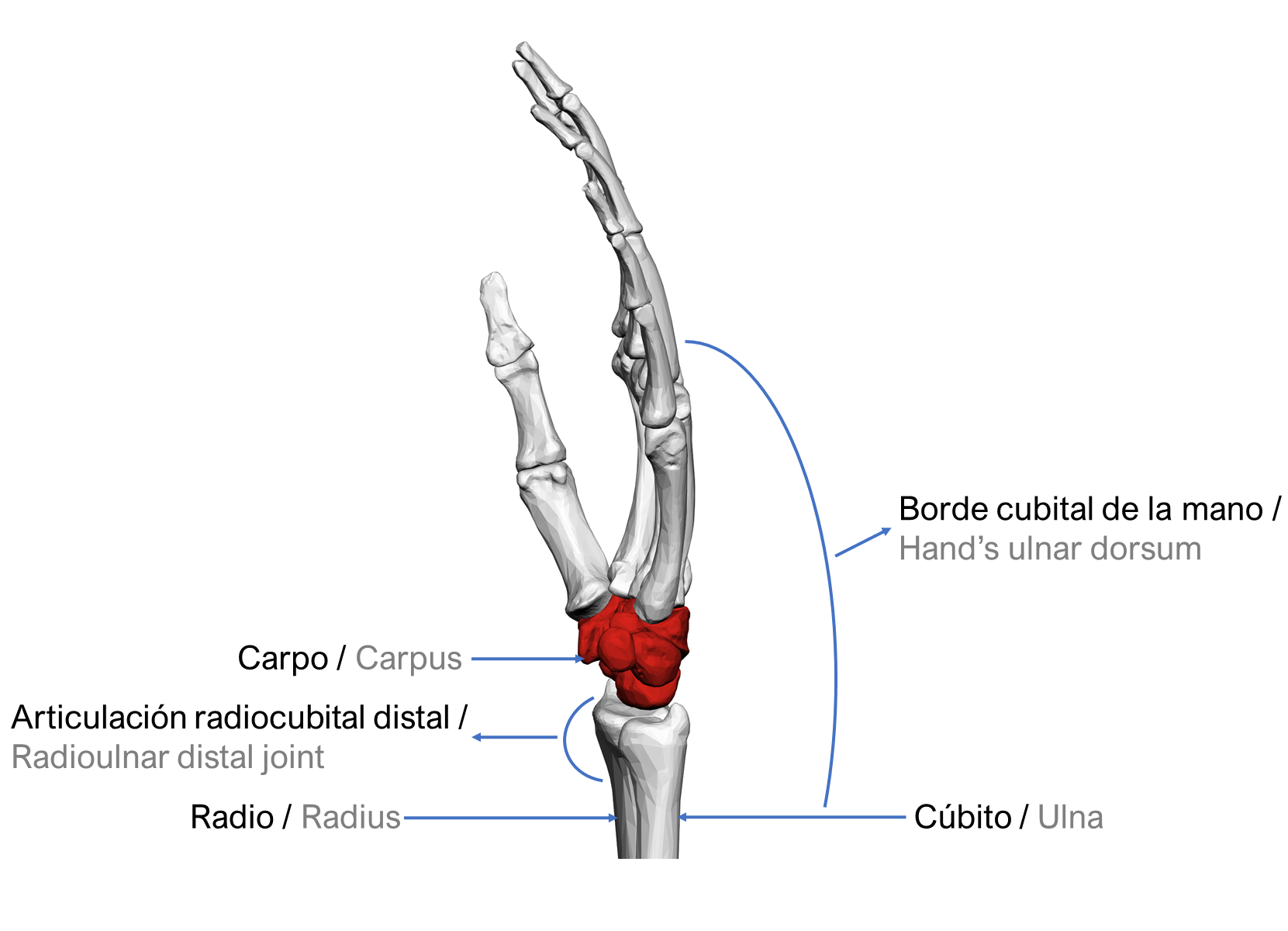

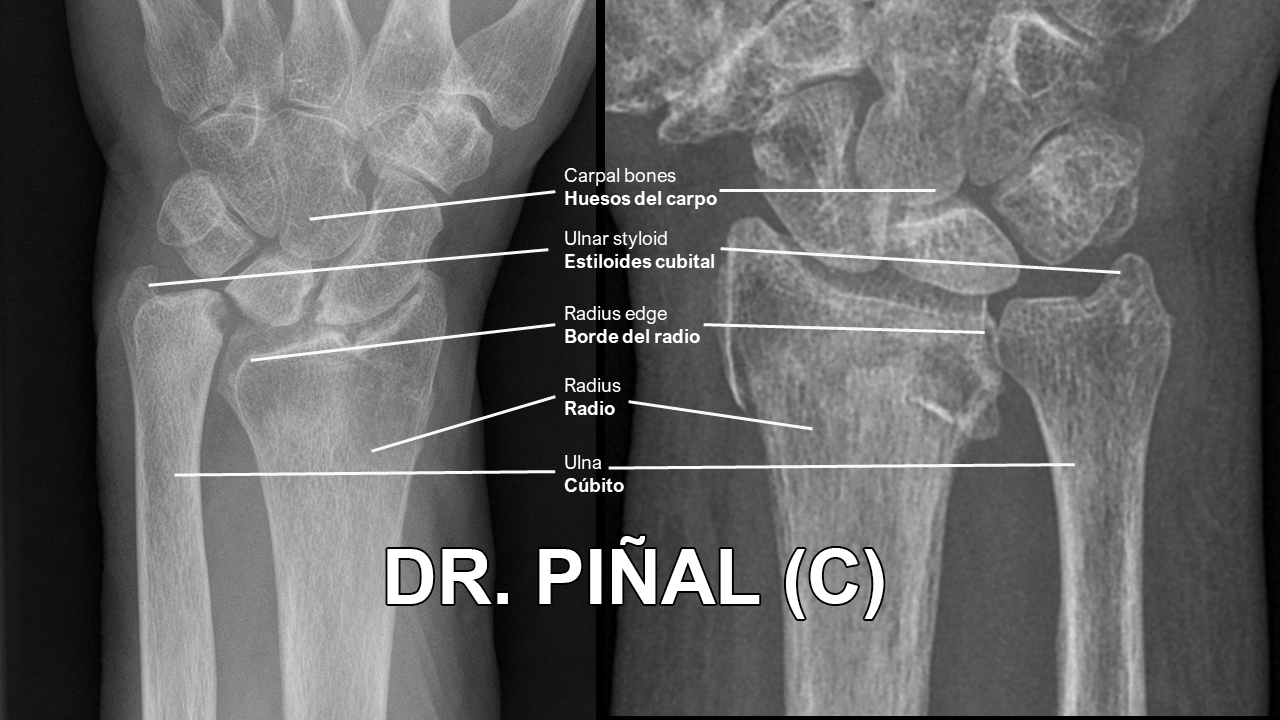

The wrist is one of the most anatomically complex parts of the human skeleton. Its location acts as a link between the forearm and the hand, with the confluence of the epiphyses or distal ends of the radius and ulna and the eight bones that make up the carpus. In this area, the ulna acts as a pivot point for the radius – the so-called distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) – which facilitates hand and wrist rotation, that is, pronation movements (the rotation that allows the hand to be positioned with the back up) and its opposite, supination. Another function of the ulna, more recognized in clinical work in recent years, is its role as a load-bearing structure in wrist movements.

Therefore, damage to the ulna and its associated structures (tendons, ligaments, etc.) can cause functional limitations and generate pain. Precisely, this last element, ulnar pain, will focus our conversation with Dr Piñal in this new post of his blog.

Dr Piñal, considered one of the world’s best hand surgeon, has developed many international presentations and medical articles in which he addresses the constellation of factors that may be found behind ulnar pain; two of his books are particularly noteworthy: ‘Arthroscopic Management of Ulnar Pain’ (2012) and ‘Atlas of Distal Radius Fractures’ (2018).

Dr, how does ulnar pain appear?

Ulnar pain manifests on the ulnar border of the hand, from the little finger and downward. When talking about this kind of pain we have to take into account a series of structures such as the ligaments or the triangular fibrocartilage (TFC) or articular disc (which will surely reappear in the conversation) that range from the ulna to the wrist and when they break or strain cause pain and mechanical failures, that is, functional problems.

In this area, pain can appear combined with instability or appear alone. In instability, the patient has difficulties squeezing and holding objects, feels clicks or cracks inside the wrist, etc. As a general rule, when it shows up, the ligamentous structures that connect ulna and radius are broken, which causes the wrist to loose and fail in pronation-supination.

We are talking about a very complex area from an anatomical perspective, right?

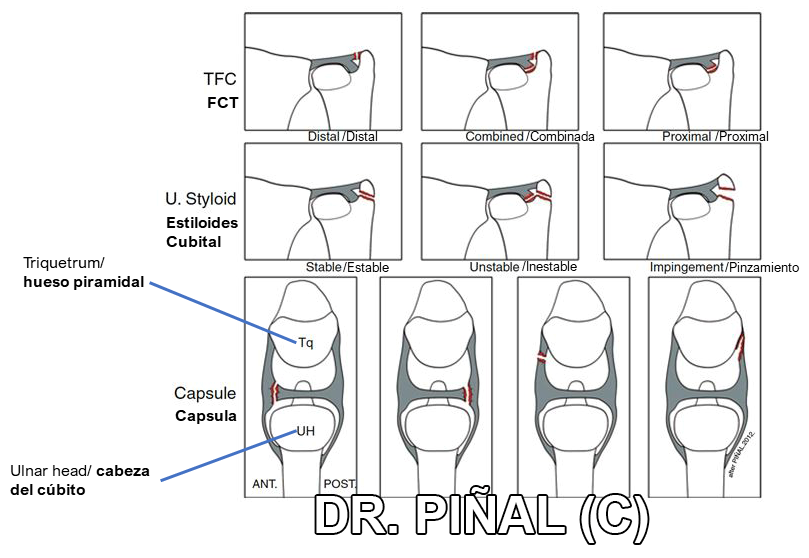

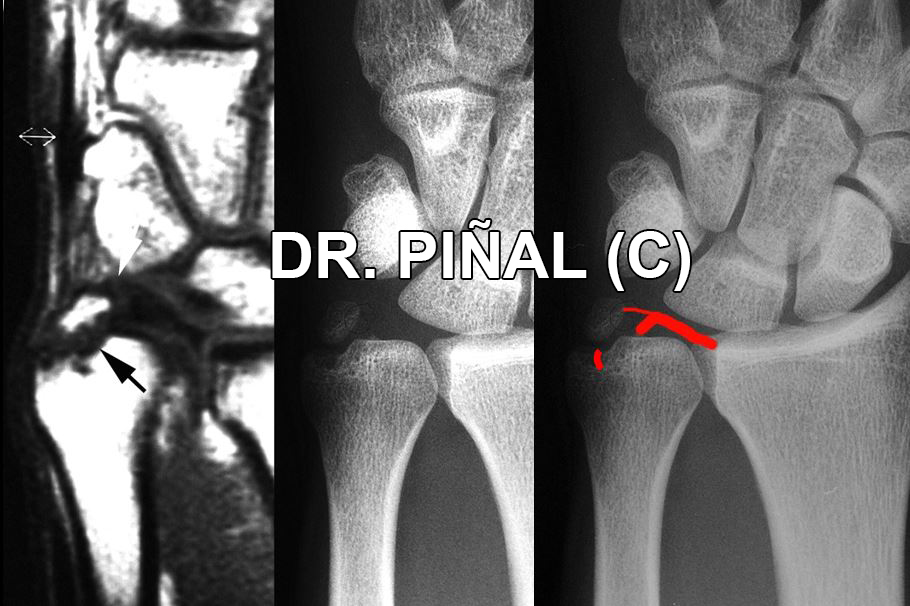

Indeed. The complexity of the area shows itself in that up to forty different pathologies can be concentrated in one cubic centimeter of the distal radioulnar joint. This is due to the convergence of multiple bone, ligamentous and tissue structures, such as triangular fibrocartilage, head of the ulna, ulnar styloid, edge of the radius, anterior and posterior capsule or extensor carpi ulnaris, among others.

Which are the most common diagnoses associated with ulnar pain?

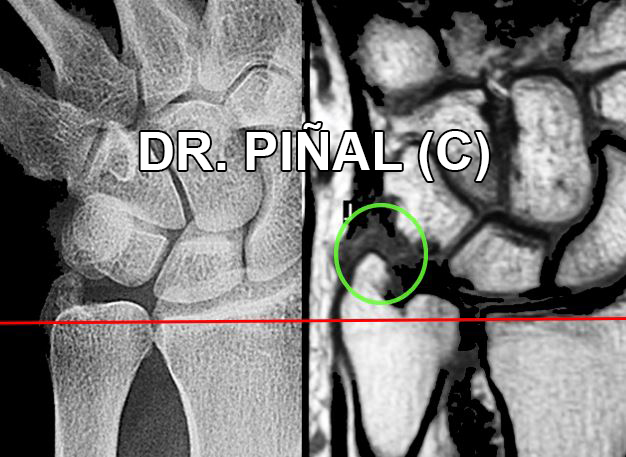

Most of the patients who come to our consultations with ulnar pain come with an MRI that shows a triangular fibrocartilage tear/rupture. They usually do it after visiting other centers or being operated on at least one previous occasion, without solving their symptoms.

At this point it would be interesting to stop at the characteristics and functions of fibrocartilage.

Go ahead, Dr, please.

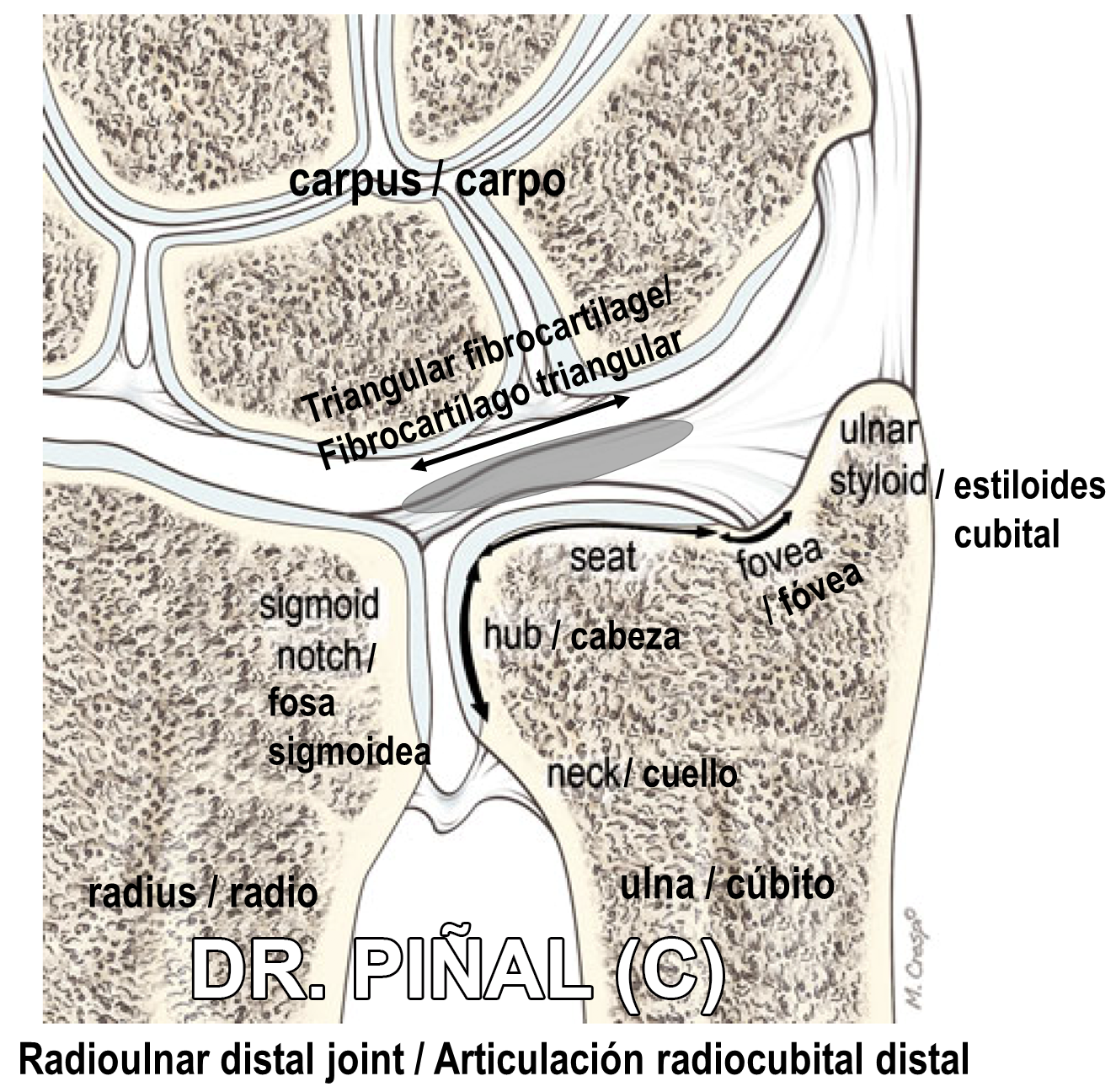

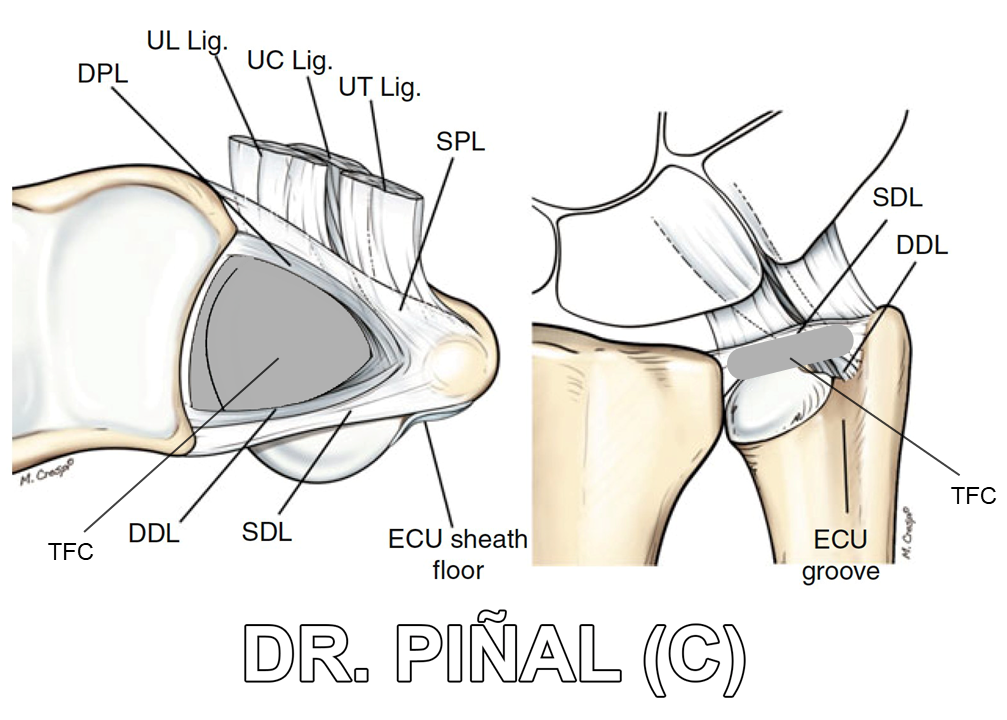

The triangular fibrocartilage is a structure composed of a combination of fibrous and cartilaginous tissues, which goes from the edge of the sigmoid notch of the radius to the fovea of the ulna, a bony cavity next to the ulnar styloid. Fibrocartilage is involved in load distribution in the upper limb and balances various complex structures in the wrist. In turn, in front and behind its triangular structure, the distal radio-ulnar ligaments are placed, which provide stability to the interactions between ulna and radius.

Furthermore, it is part of the so-called triangular fibrocartilage complex (CFCT). This is formed by a combination of non-bony elements such as the fibrocartilage itself, the aforementioned radio-ulnar ligaments, the ulnolunate ligament or the tendon sheaths, which together provide stability to the distal radioulnar joint and separate it from the wrist bones (carpus) and the distal segment of the radius, allowing us harmonic movements and strength in the grip

However, triangular fibrocartilage isn’t the most common origin of the pathologies that cause ulnar pain in the patient. Despite its usual presence in the initial diagnoses and the erroneous comparison of its role with that of the meniscus in the knee, fibrocartilage tears are behind the mentioned conditions in just about 20% of cases.

Likewise, it doesn’t usually present in an isolated way, but rather it does so in combined forms together with other injuries such as wrist fractures.

For this reason, it’s common for patients operated on only for fibrocartilage to continue presenting pain, after a procedure in which the other convergent ailments have not been treated.

Going one step further, we can affirm that the rupture of the triangular fibrocartilage is a physiological fact for most patients, affecting 30% of the population over 30 years without generating medical problems.

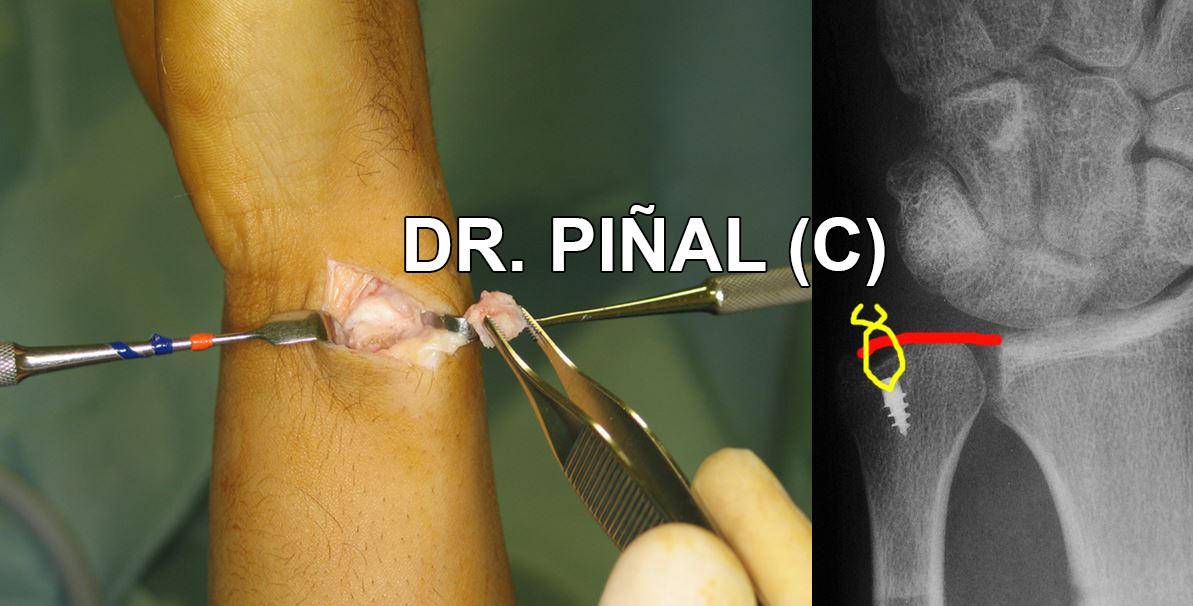

Case study 1.2: the video shows Dr Piñal raising the fibrocartilage and thus showing that it is loose with respect to the fovea. In this case, arthroscopy is key in identifying the injury.

The clinical context changes in cases of intensive use of the wrist, such as in professional athletes, with more specific demands (strength, grip, etc.), for whom the fibrocartilage injury is especially limiting given its role in the absorption and distribution of the force exerted when clenching the fist or grasping an object (the following video presents one of these cases: the posterior rupture of the fibrocartilage in a professional climber).

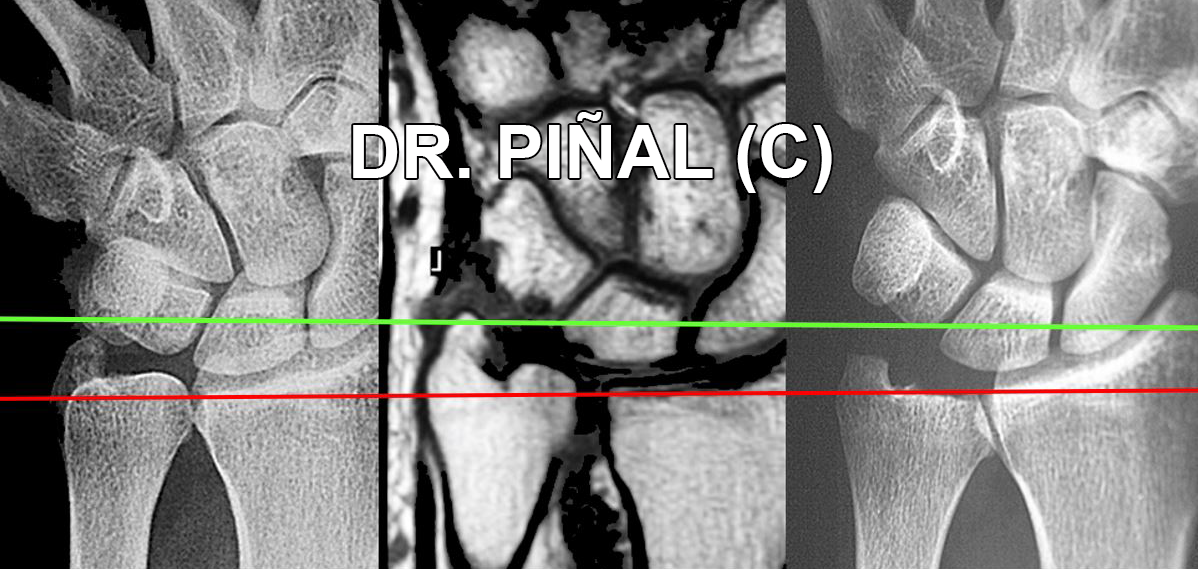

We have a similar situation with patients whose diagnosis describes an ulna longer than normal or ulna plus, which exceeds the radius in length. This happens to 20% of the adult population, without necessarily assuming any ailment exists, and may be behind fibrocartilage tears. The ulna plus is pathological when it impacts with the ulnar carpal area, especially with the lunate bone, causing the so-called ulnar impaction syndrome and becoming a source of ulnar pain and other processes such as cartilage delamination.

Case study 2.2: the arthroscopy shows the triangular fibrocartilage ‘shredded’ by the impacts derived from the position of the head of the ulna and the ulnar styloid.

Taking into account what you have just explained, why this high diagnostic presence to which you alluded?

Broadly speaking, because the rupture of the triangular fibrocartilage is what is most seen in an MRI. As I have said on other occasions, medical tests are interpretable and are not a dogma, so they must be combined with other aspects such as examination or analysis of the patient’s history.

Which are the most frequent pathologies behind ulnar pain, then?

The most common, and also the most benign, is ulnar pain related to ligament injuries: sprains on the ulnar side of the wrist. These overstretches or tearing of the ligaments (depending on their intensity) can produce scar tissue that, with the movement of the wrist, comes into friction with other bone or ligamentous structures, causing erosions, irritation, inflammation and pain. Also, in the most severe cases, they cause instability in the distal radioulnar joint as a whole.

We are talking about ligaments such as those connected to the ulnar styloid or the head of the ulna, to name a couple of examples.

Second in frequency, would be the ulnar pain related to the length of the ulna or, more specifically, of the head of the ulna and the ulnar styloid. Both can collide with the bones of the wrist, causing the impaction syndrome that we mentioned earlier. In some movements, such as the backward movement of the wrist in supination, this becomes a focus of inflammation and pain.

Then, thirdly, we would address the sequelae of radius fractures in the ulna, caused by subsequent anatomical imbalances in the position of the latter with respect to the ulna: lower, inclined, sunken, etc.

These sequelae can be masked at a diagnostic level as fibrocartilage tears (which, as we have already said, appear in all wrist fractures), when in reality the origin of most of the pain and functional difficulties is the position of the radius.

It should also be noted the tendonitis of the extensor carpi ulnaris, with ruptures or inflammation of the groove, that is, the displacement channel of the tendon, which causes it to come out; in addition to capsular tears, damage to the wrap around the wrist that facilitates contact between the articular surfaces.

Finally, another noteworthy pathology is post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the distal radioulnar joint, that is, the degenerative process of the joint linked to unresolved fractures in the area.

However, and I return to the idea of the complexity of the area, in the generation of pain several ailments can converge simultaneously: a sprain and an inflammation caused by the ulnar styloid, for example.

In this cubic centimeter, to which I referred, when a trauma occurs many things tend to break. For example, the ulnar styloid, the insertions of the triangular fibrocartilage, and, in addition, the ligaments between the pyramidal bone and the ulna can rupture at the same time.

It is key to bear in mind that if the multiple aspects of each injury or pathology are not addressed, the patient will not be well.

When is surgery involved in the resolution of these injuries?

Many ulnar injuries heal on their own without the need for surgery, through conservative treatment (rest, anti-inflammatories, physical therapy, etc.). However, in our case, as I mentioned, it is different since we usually see patients without a clear diagnosis or already operated unsuccessfully, with provokes the frequency of surgical procedures to increase.

In turn, there are injuries that from the beginning involve surgery, with a better prognosis if they are operated at an early stage. Its treatment in the acute phase can prevent its chronification.

Overall, the main approach used is dry arthroscopy intervention, which facilitates greater diagnostic precision and reduces recovery times, combined with techniques that we have developed over time such as intra-articular suturing (all-inside suturing), among others.

Arthroscopic suture of the articular fibrocartilage “from within”, a technique by Dr Piñal published by the European Edition of the Journal of Hand Surgery.

The most common procedure is debridement of partial ligamentous tears and capsular tears. We can also highlight the intervention on imbalances in the relationship between the ulna and the radius, either from birth or caused by fractures of the latter. In this case, the most usual is to have to act on the radius and then adjust the ligaments that attach it to the ulna.

Next, but at a distance in terms of prevalence, is the surgery aimed at solving distal radioulnar instability due to ruptures of the insertion of the TFC ligaments in the fovea of the ulna.

Related content:

es

es en

en fr

fr it

it ru

ru zh-hans

zh-hans